The Competition Bulletin is pleased to welcome the second in a three-part series of blogs on Brexit and merger control by Ben Forbes and Mat Hughes of AlixPartners. Ben and Mat are (with others) co-authors of the new Sweet & Maxwell book, “UK Merger Control: Law and Practice”.

Part one focused on the voluntary nature of UK merger control and can be found here.

Introduction – the CMA’s mergers workload will increase

At present, UK mergers that meet certain turnover thresholds fall exclusively under the jurisdiction of EU Merger Regulation[1]. However, Brexit is likely to end this “one-stop” merger control regime for UK companies, leading to more mergers being caught by UK merger control.

To put this in context, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) published 72 decisions concerning qualifying mergers in 2014/15, and 60 such decisions in 2015/16. Even 20 or 30 more UK merger decisions would therefore represent a very substantial increase in the CMA’s workload, and large-scale European mergers may impact multiple UK markets. The CMA’s workload will further increase as Brexit will also mean that the UK authorities acquire sole responsibility for enforcing all competition law in the UK.

This part of our blog series focuses specifically on two particularly poor, but often-discussed, options for reducing the CMA’s mergers workload (i.e. what not to do):

- Removing the ‘share of supply’ test; and

- Integrating the CMA’s Phase 1 and Phase 2 review teams.

The reason for this starting point is that the UK merger control regime has been subject to extensive fine-tuning in recent years, and it is important to ensure that future changes do not compromise the efficacy of the regime.

The third part of this blog series will focus on much more sensible options for adjusting UK merger control.

Should the CMA look at fewer mergers, and is the ‘share of supply’ test an appropriate jurisdictional threshold?

As set out in the first part of this blog, the CMA focuses more of its investigations on anti-competitive mergers than under the EU Merger Regulation. Nevertheless, another distinctive feature of UK merger control is that mergers may qualify for investigation where the merger creates (or enhances) a market share of 25% or more in the UK, or a “substantial part” of the UK (the so-called “share of supply” test). They may also qualify where the UK turnover of the target firm exceeds £70 million (the “turnover test”).

The share of supply test can be applied very narrowly at both:

- The product level – This is because the share of supply test is based on the “description” of goods and services. These descriptions can be very narrow and do not need to correspond to economic markets; and

- The geographic level – Small parts of the UK (such as Slough), which the CMA considers to be a “substantial” part of the UK.

The share of supply test often creates uncertainty for the parties. Often they do not know the products and geographic area over which the CMA will apply the test. They may also not know their competitors’ sales, making market shares difficult to calculate. It is therefore legitimate to question whether the share of supply is an appropriate jurisdictional threshold.

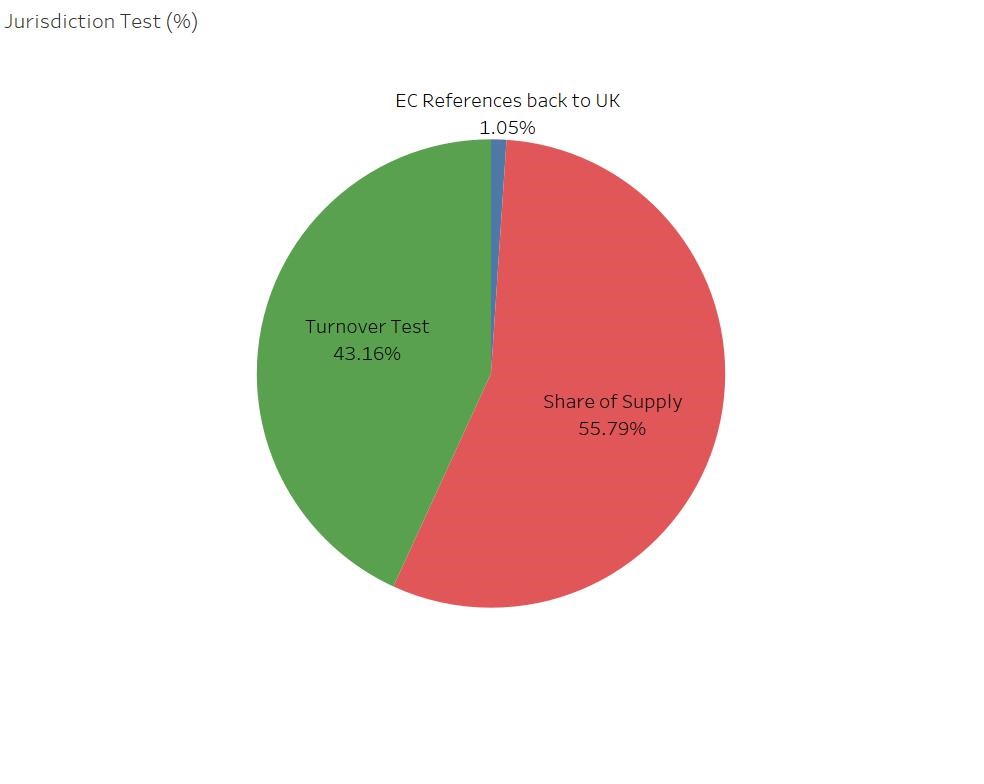

However, we believe there are two good reasons for retaining the share of supply test. First, the share of supply test captures effectively mergers that may be problematic. From 1 April 2010 to 30 September 2016, 56% (53 cases) of the 95 Phase 1 merger cases that were either cleared subject to undertakings in lieu of reference or referred only qualified for investigation under the share of supply test. Abandoning the share of supply test would therefore grant a “free pass” to these mergers – unless the turnover test is reduced.

The jurisdictional basis of Phase 1 merger cases either cleared subject to undertakings in lieu of reference or referred

Source: AlixPartners analysis

Second, the share of supply test is a highly effective and focussed way of enabling the CMA to investigate mergers that may lead to a SLC. In particular, UK merger control focuses on mergers that create or enhance high market shares, or that reduce the number of competitors from four to three (or fewer). Between 1 April 2010 and 31 March 2016, 94% of Phase 1 mergers where undertakings in lieu were accepted or the merger was referred, involved horizontal mergers between competitors where:

- The merger created or enhanced high market shares of 40 per cent or more;

- The merger reduced the number of competitors from four to three (or fewer), or where the merged undertaking’s market share exceeded 35% (calculated on various different bases).[2]

Should the CMA be fully integrated such that there is no distinction between the review teams at Phase 1 and Phase 2?

Creating the CMA as a single, integrated competition authority was intended to yield various synergies. In particular, the CMA has responsibility for both Phase 1 merger review (previously carried out by the Office of Fair Trading) and Phase 2 merger review (previously carried out by the Competition Commission). However, a clear distinction between Phase 1 and Phase 2 has been retained. In contrast to most other competition authorities, at Phase 2, a new case team is appointed, with largely separate staff to Phase 1 and the decision makers at Phase 1 are not involved at Phase 2. The purpose of this structure was to retain the independence of the decision makers at Phase 2, with the CMA Panel making the final decisions at Phase 2.

The particular concern is that an integrated Phase 1 and 2 process would suffer from “confirmation bias”, namely a case team finding a competition problem at Phase 1 may be predisposed to follow suit at Phase 2.

The CMAs’ costs, and possibly those of the parties, could be reduced to some degree by dispensing with the separation of the Phase 2 and Phase 1. However, as the government indicated when it created the CMA, the independence and impartiality of the Phase 2 regime is a particular strength of UK merger control. Whilst the government consulted in May 2016 on the precise structure, identity and number of CMA panel members, there are strong arguments for retaining the independence and impartiality of the CMA panel.

Conclusions

Notwithstanding the inevitable increase in the CMA’s workload we would not recommend either:

- Abandoning the share of supply test. This test is a strength of the UK regime as it focuses UK merger control on mergers that experience suggests are most likely to lead to competition concerns; or

- Changing materially the independent and impartial nature of the CMA in relation to its investigation of Phase 1 and Phase 2 mergers.

Part three of this blog series considers, in our view, much more sensible adjustments to UK merger control to reduce the CMA’s workload without compromising its effectiveness.

[1] There are provisions for mergers to be referred down to individual member states and up to the Commission from member states.

[2] See further s.6-009 of “UK Merger Control: Law and Practice”, Parr, Finbow and Hughes, Third Edition, Sweet & Maxwell, November 2016.

One response to “Brexit and implications for UK Merger Control – Part 2/3: Implications for the CMA’s workload and what not to do”

[…] Part one focused on the issues associated with the voluntary nature of UK merger control (and can be found here), and part two considered options for change that in our view should not be adopted (and can be found here). […]